hammajang luck - entering the cozy sff uncanny valley

2026-02-15

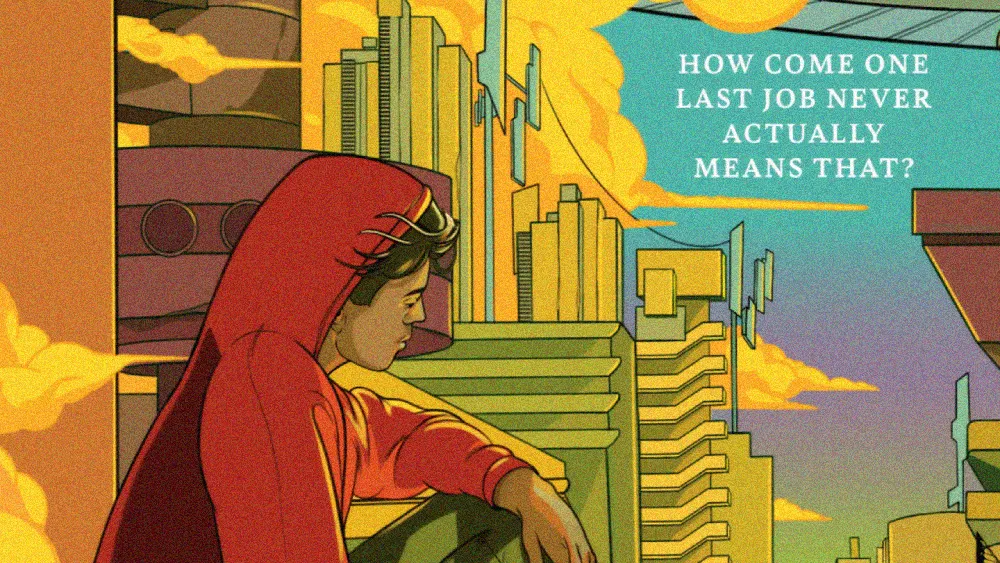

Edie Morikawa is a thief doing time in a space prison. Climate collapse and rising sea levels have forced many Hawaiians into space, where they eke out an existence on the margins of society on the Kepler station. Edie’s last job went belly-up, and they were sold out by their partner-in-crime and childhood sweetheart, Angel, earning Edie an eight-year prison sentence.

To Edie’s surprise, they’re let out early. Angel is behind this, too; she’s making Edie an offer they can’t refuse. Angel’s spent the last few years ingratiating herself to a Elon Musk-esq tech CEO, and she wants Edie to join her crack team for their biggest job yet: scoring on Angel’s boss. Edie’s desire to prove to their family that they’re done being a crook is overcome by their desire to provide for them materially, and thus they tumble back into Angel’s web.

Makana Yamamoto’s 2025 debut Hammajang Luck is a breezy queer sci-fi heist story described by its publisher as “Ocean’s 8 meets Blade Runner.” Half of that comp is accurate; I’ll let you guess which.

I wasn’t going to write this review. Despite my contrarian nature, I like to like things, and I don’t enjoy being sour grapes about work by a queer debut author.

I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed.

There were things I liked about Hammajang Luck. The Hawaiianness of the characters’ world felt to me, an outsider, deftly handled and warm. The basic premise is engaging. I’m not so hardened as to be unmoved by the novelty of reading a book whose protagonist uses the same pronouns I do without it being a whole thing.

Nevertheless, my reading experience was marked by a sense of unease. I couldn’t relax into the story, but not due to suspense; it was obvious that no lasting negative consequences were coming for the characters we’re supposed to like. It’s a crime caper, not a dramatic novel about crime and punishment, and this tone is accurately reflected in its marketing (if you guessed Ocean’s 8 as the accurate comp earlier, congratulations.)

Despite knowing better, I kept hoping for a subversive twist. I entertained the possibility of a pivot wherein the story would get incredibly and self-consciously dark, like a delayed onset Madoka Magica situation. I’d applaud it for bait-and-switching the audience with the trappings of 2010s-2020s cozy sff before confronting the reader with violence and loss. This idea was so entrancing I kept the faith until late in Hammajang Luck’s second act.

Sadly, this would never happen, because the state of things in the sff critical space is such that a book pulling that move would be harshly criticized by a good part of the audience for being mean-spirited and manipulative. The implied contract with the reader is inviolate and we like it that way.

As it stands, Hammajang Luck delivered what it promised: a heist story featuring a diverse cast of mostly queer characters engaging in high-tech Robin Hood antics. This is not inherently a bad thing, though grittier criminal action storytelling can be found in Artemis Fowl, and I don’t feel it’s unreasonable to expect an adult sff novel to play for tougher stakes than middle grade books about fairies.

Despite Hammajang Luck aiming for frothy caper, I was never able to turn my brain off and meet the novel on its own terms. The barrier was not the tone, or the coziness, or the saccharine found-family everything-is-going-to-be-okay posture the story assumes from the start, but the incongruence between those story elements and the substance of the plot. Hammajang Luck led me through an uncanny valley in which cyberpunk space dystopia feels like a more comfortable and forgiving place to live than most places on the globe in 2026. It depicts a world in which sending someone to prison for years and then releasing them only to coerce them into joining a criminal enterprise will be water under the bridge in 300 pages flat. All it takes is hitting some childhood-friends-to-lovers story beats and gesturing at a sense of remorse from the person responsible. Angel goes to prison herself for a few years at the end of the novel, and after that, they’re even Steven. Trauma, what trauma?

To be clear, my issue with Hammajang Luck isn’t that it’s problematic. It’s that it’s not problematic enough.

I could write a lazy and easy version of this post that scolds people for their aesthetic preferences. Here’s what that would look like:

I’m sorry if you like nice things. Sorry if you pick up a work of queer sci-fi looking for a moment of respite from the onslaught of human suffering to which we are all witness. Sorry if you want to feel good for once in your life. It’s allowed. It’s legal. I cannot take it away from you. But oh my god sometimes I wish I could.

I say lazy, because the aesthetic qualities of a work don’t carry inherent moral valence. Lots of works of queer edgelord art are trite. And the tone is not the problem with Hammajang Luck—truly. It’s a symptom.

While writing this review, I’ve repeatedly capitulated to the voice in my head saying It sounds like it just wasn’t for you by starting sentences with phrases like, “To be fair, I’m not the target audience for this work.” But this is not true.

I’ve recently been listening to the Friends at the Table season Twilight Mirage, which is a story about a utopia in decline and the people fighting to save it. Its cultural touchstones include classic cyberpunk as well as Studio Ghibli and the music of Frank Ocean; its aesthetic sensibility centres loss and melancholy alongside beauty, compassion, and pride. It features a highly diverse ensemble cast and asks how a human diaspora in space could or should maintain a connection to Earth. I find it resonant and moving, and have never thought to myself, “Wow, I wish this was more grim.”

Back to the topic at hand.

I understand in the abstract why someone would write a cyberpunk heist story that prioritizes fun over gloom. I just ask that works be internally consistent. I need to trust that an author has thought through the implications of the events they depict, whether or not they dwell on those implications. Focusing on suffering isn’t necessary, but I need to feel that the author is aware that deep suffering is possible. I have to be able to maintain emotional suspension of disbelief. Failure to do this produces an incoherent story structure where I cannot care about anything that happens, because the author has not made me care, because things do not matter. This is a structural flaw that undermines the integrity of the rest of the work.

If the novel’s central romance involves one character having sent the other to space prison for years, I need to feel the gravity of that history weighing on them. I can still believe they’re in love and will choose each other, but god, they should have to fight for it.

I kept expecting Hammajang Luck to reveal that Angel actually hadn’t been responsible for sending Edie to prison and just couldn’t tell Edie the truth because Reasons. My brain tried to square the circle of how Yamamoto could set up such a twisted dynamic only to no-sell it completely. In reality, the degree of animosity Edie and Angel show each other in the novel feels proportionate to how you might feel toward your ex who got you fired from a job, or got you cut out from a friend group, or cheated on you.

I’m struggling to articulate my criticism beyond “incarceration is deeply traumatizing and life-changing and I need to feel that the story understands this.” I’m sure Yamamoto is aware of the reality of this statement, but that knowledge should be inextricably woven into the emotional fabric of the story.

To fix this story, one of two revisions would need to have been made:

- Edie and Angel’s backstory is changed such that Angel is not the reason Edie went to prison. However, the released-from-prison-to-do-one-big-dangerous-job setup tidily sets up the plot and provides context for the rest of Edie’s relationships, as well as the central forced-to-work-together, reconciliation-romance with Angel. This change would require a massive rewrite. The least obtrusive angle would be the “Angel had to pretend she sold out Edie but actually didn’t” copium my brain dreamed up when I still wanted to believe I could like this book, but even that would require significant work to justify the contrivance.

- The story’s orientation toward crime, incarceration, and consequence is changed such that what Angel did to Edie is treated as deeply violent. The connections between interpersonal and state violence are drawn. The possibility of doing great harm to people you love is taken seriously.

When I say the tone is not the problem, just a symptom, I mean that a story taking the latter position could also contain hi-jinks and levity and be oriented toward hope. It wouldn’t necessarily require the removal of Edie and Angel’s reconciliation-romance. But it would require the story to be willing to make some readers uncomfortable by sitting with the contradictions instead of pretending they’re not there.

To be clear, my issue is not that the dynamic at the heart of Hammajang Luck is wildly toxic. I love toxicity. The book just doesn’t seem aware of how toxic the dynamic is, or at least is not willing to engage with it seriously. Its reluctance to depict sympathetic characters as being capable of ugliness and serious harm dooms the novel, because the ugliness and the harm is already there; Yamamoto just hasn’t convinced me they’ve considered the implications of their own narrative.

Now, I don’t want Hammajang Luck to be dour and self-serious or precious about its depiction of incarceration and relational harm. I don’t want it to pat my hand and reassure me it knows that these things are Very Bad. I would complain about that, too (I’m hard to please.)

One of Twilight Mirage’s first story arcs revolves around a prison. Specifically, it asks what a prison would look like in a utopian society, and what happens to the people inside when the institutions that stewarded it begin to collapse. It’s not misery porn. It doesn’t beat the audience over the head with the horrors of the prison-industrial complex. It trusts that the audience is aware of that reality. That awareness colours the story that is told; it contextualizes the stakes.

What I’m getting at is that the reality of incarceration can hang over a narrative without sordid flashbacks or didactic lecturing. It’s about the weight you put on the things you do show. Make things matter.

A few days ago, I watched Michael Mann’s 1995 classic action-drama crime film Heat. I liked it very much. The way in which I liked it led me back here, to write about a book I wish I liked, that I tried hard to like, but did not.

Heat follows the cat-and-mouse game between hotshot LAPD detective Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) and brilliant leader of a crew of expert thieves, Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro), as McCauley’s crew rack up a string of high-profile robberies and heists.

During McCauley and Hanna’s first face-to-face conversation, halfway through the film, my housemate walked past the TV. “It’s the beginning of their romance,” I said. “A very brusque romance,” she replied. Indeed.

Hanna: Seven years in Folsom. In the hole for three. McNeil before that. McNeil as tough as they say?

McCauley: You looking to become a penologist?

Hanna: You looking to go back? You know, I chase down some crews; guys just looking to fuck up, get busted back. That you?

McCauley: You must’ve worked some dipshit crews.

Hanna: I worked all kinds.

McCauley: You see me doing thrill-seeker liquor store holdups with a “Born to Lose” tattoo on my chest?

Hanna: No, I do not.

McCauley: Right. I am never going back.

Watching Heat, I found myself longing for butch Vincent Hanna. Hanna Vincent, let’s say. “I got a wife. We’re passing each other on the down-slope of a marriage—my third—because I spend all my time chasing guys like you around the block. That’s my life…” Then I started imagining what the story would be like if all the macho cis guys were queers of some form or another, still getting up to all the same business. Then I remembered this book I read last summer, that I picked up despite knowing it would probably disappoint me, because I wanted to believe it would give me that juice.

Now, Hammajang Luck is not trying to be Heat. The Ocean’s 8 comp is accurate; it’s a pleasant and unchallenging caper that banks on the novelty of a diverse cast to make up for the lack of vitality in its execution. But there’s enough overlap in subject matter I find the comparison illuminating.

Heat is not about the prison-industrial complex, and neither does it offer profound sociopolitical commentary. Prison within its narrative represents the loss of freedom, an enclosure from choice and possibility. For the members of McCauley’s crew, most of whom have already been exiled from straight society due to past convictions, the “freedom” available outside of the pen is a death spiral; the deeper they go, the harder it will be to ever extricate themselves. It’s the classic existential paradigm of crime fiction. All that lies at the end of the road is a choice between two forms of oblivion.

The film ends with Hanna chasing McCauley in the dark through back lots of LAX. After several agonizing minutes, the lights of a descending plane illuminate McCauley, and Hanna shoots him several times in the chest. They lock eyes. Hanna approaches, and he holds McCauley’s hand as he bleeds out.

McCauley: Told you I’m never going back.

Hanna: Yeah.

This is romance; a brief moment in which two souls know and see each other wholly, not in spite of the violence that brings them together but because of it. Our butch antihero Hanna Vincent is fully aware that without the hunt, they are nothing; they’re a shadow of a person, and their own freedom is limited to chasing crooks in order to justify their own existence. This is a narrative that has followed its characters’ trajectories to their logical conclusion.

I don’t know which works influenced Yamamoto during the writing of Hammajang Luck. They might hate movies about macho dudes in rooms talking at each other intensely and sometimes blowing stuff up. But if they wanted to write a screwball heist comedy, they could have done so. They did not. They wrote a cyberpunk novel about the harsh choices faced by queer career criminals belonging to a diasporic underclass, but shied away from depicting anything harsh.

Many such cases, unfortunately.

So, if this story isn’t “for me,” who is it for? How does a novel like this come into being?

Hammajang Luck has been generally well-received. A healthy contingent of readers of contemporary progressive/queer sff are looking for diverse genre fiction that is fun and uplifting. But this is where I start to feel insane, because I want that too, (albeit not exclusively.) I just also want the books I read to be good.

There is a likeability crisis in much contemporary queer sff. Authors are unwilling to make their characters look bad, and it compromises the integrity of the story. I don’t think this is the result of individual authors’ incompetence. The state of the publishing industry and the social media ecosystem around genre fiction has refigured the reader as, primarily, a customer, and the customer is always right.

If Yamamoto had written a highly entertaining and optimistic crime novel with a cast of highly flawed marginalized people who the reader is expected to root for even as they hurt each other, themselves, and the people around them—if they took seriously the premise of the story they did in fact write—it may have been more difficult to market. It may have received more negative Goodreads reviews from the kind of people who don’t like Wuthering Heights because it’s just a bunch of terrible people treating each other terribly. But oh my god. Who cares. Those people can go read a book that isn’t about people who steal things for a living and send each other to jail.

Expecting authors to honour the gravity of their own concepts is not in conflict with appreciating fun, escapist genre fiction. Why are the “let people enjoy things [and don’t say anything negative about the things they enjoy]” crew the only ones who deserve to enjoy anything?

So much cozy-adjacent sff fails by prioritizing a perceived obligation to give the reader what they want over a commitment to respecting the reader.

You have got to believe in your story. You have got to believe that the reader doesn’t know exactly what they want, because they want to be surprised in a way that brings pleasure and enjoyment, and that you as the author are capable of achieving that for at least the majority of good faith readers.

It is impossible to make art that everybody likes. It is impossible to make art that doesn’t make anyone uncomfortable, because humans are idiosyncratic. The attempt to make your story comfortable for the maximum number of readers siphons the potency of your art.

It’s not about having an antagonistic relationship to your readers, or trying to get one over on them. Part of respecting your readers is respecting their intelligence and maturity; you trust them to handle the feelings your story might evoke. You trust yourself, as the author, to tell a story that is charismatic enough to justify its existence.

It is very hard to say something meaningful without acknowledgement of the abyss: loss, isolation, suffering, all the other universals of human life. You don’t have to dwell on the abyss. You don’t have to look into it or say its name. A story can be sweet and encouraging and suitable for children of all ages and still refuse to cut its characters, or its world, a break. I want to feel kinship in the messy feelings, the ones that are hard to hold outside of art. I want to feel that other people have felt this way, too. That we’re not all just skirting our eyes around the abyss and going on with our day as if it isn’t there.

Everything else feels like an advertisement.